The Autonomous Human Risk Management Platform

Replace manual security awareness programs with an AI engine that automates phishing simulations, training, and risk remediation.

Security awareness shouldn't be a compliance checkbox. PhishFirewall uses AI to automate training, eliminate administrative busywork, and measurably reduce risk. Give your team their time back while hardening your human firewall.

Tired of the endless cycle of ineffective training? So were we.

The Old Way:

A Familiar Story

For decades, security awareness has been treated as a compliance checkbox, not a strategic initiative. The result? Frustrated security teams, resentful employees, and zero measurable improvement in risk.

Bob

IT Director

"Drowning in manual overhead. Spending Friday afternoon setting up generic simulations instead of strategic initiatives."

Hover to solve

Fully Autonomous AI

The PhishFirewall Way

Bob went home early. Lora handled the simulation setup, scheduling, and remediation automatically.

Elizabeth

Accounts Payable

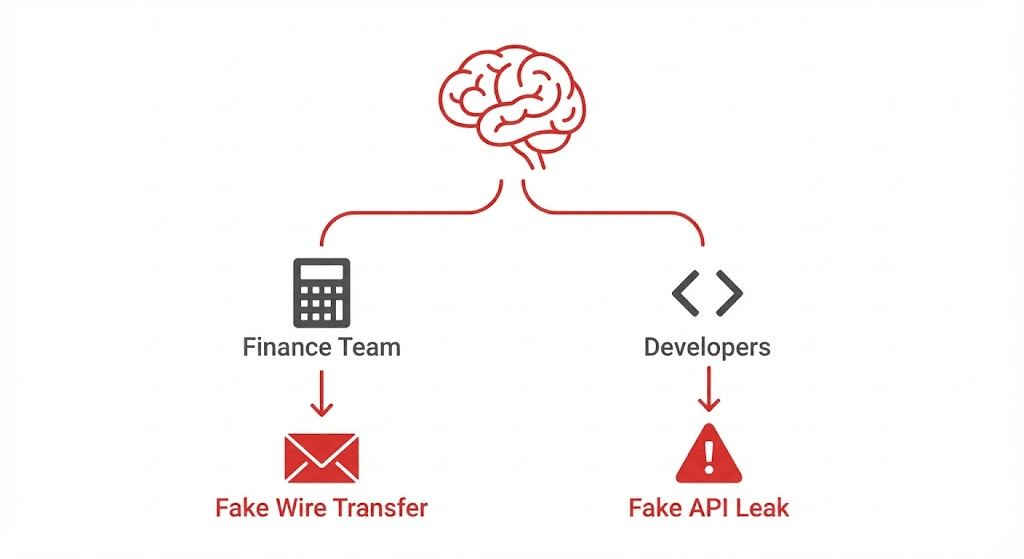

"Clicks a suspicious travel email because the 'one-size-fits-all' training never taught her about specific finance threats."

Hover to solve

Hyper-Personalized

The PhishFirewall Way

Lora recognized Elizabeth's role. She received a specialized 'Wire Fraud' simulation instead of generic spam—and she spotted it.

Joe

Sales Team

"Enraged by boring, generic phishing tests that waste his time. He ignores IT's emails and hates the 'gotcha' culture."

Hover to solve

Gamified & Positive

The PhishFirewall Way

Joe just earned a 'Cyber Rockstar' badge. He watched a 45-second, Netflix-style clip that actually respected his time.

The PhishFirewall Way:

AI-Powered, Personalized & Positive

PhishFirewall represents a strategic shift from a tool you manage to a solution that works for you. Our platform is built around an "agentic AI"—a fully autonomous agent named Lora.

Agentic Human Risk Management

Fully Autonomous AI Agent

Lora handles everything. She assesses users, deploys training, and runs simulations. Zero simulation management required.

Adaptive Learning Paths

A generic approach is an open invitation for a breach. Lora acts as a personal security tutor, tailoring simulations and training to each user's role, risk profile, and past performance.

"Smart Reflexes"

Short, engaging, "TikTok style" videos (<60s) build subconscious reflexes, not just knowledge.

Click to see Lora in action ▶

Instant Feedback & Positive Reinforcement

We celebrate success and use mistakes as teaching moments. Elements like leaderboards, badges, and progress tracking boost motivation and friendly competition.

🎉 Cyber Rockstar!

Threat Reported Successfully

+50 Security Points

How It Works: Simple Setup, Powerful Automation

PhishFirewall is designed for maximum impact with minimum effort. Up and running in less than an hour.

1. Connect Your Environment

Securely sync your user directory (Microsoft 365 or Google Workspace) with a simple, read-only OAuth application.

2. Let Lora Take Over

Lora begins assessing vulnerabilities and deploying personalized simulations. No simulations to manage.

3. Measure Risk Reduction

Track progress via a single dashboard. Monitor click rates, reporting, and engagement in real-time.

The Science of Secure Habits

Traditional training fails because it ignores how habits are formed. PhishFirewall is built on proven psychological principles, like the BJ Fogg Behavior Model, to drive real behavior change. We focus on Motivation, Ability, and Prompts to make secure habits second nature, not an afterthought.

Building Reflexes, Not Checking Boxes

Annual training is forgotten in weeks. We build lasting security reflexes through a continuous cycle of realistic phishing simulations and bite-sized microlearning modules that fit effortlessly into the workday. This ongoing practice ensures your team is always prepared.

Security That Works Where You Work

The best security tools are the ones people actually use. By embedding tools like our one-click email reporting button directly into the employee's daily workflow, we reduce friction, increase participation, and turn your entire workforce into a human firewall.

The Difference is Clear

See why leading organizations are switching from legacy training to the PhishFirewall platform.

Our Commitment to Your Success

We don't just sell software; we deliver a partnership focused on measurable risk reduction.

Sub 1% Phish Click Rate Guarantee

We commit to driving your click rate below 1% within 12 months. If not, we provide free consulting to fix it.

90-Day Satisfaction Guarantee

Try PhishFirewall risk-free. If you're not satisfied within 90 days, we'll provide a full refund.

See What You Save When You Fire

"Check-The-Box" Training

Stop managing simulations. Start managing strategy.

IT Hours Reclaimed

332

hours per year

No more manual simulation setups, reporting, or chasing repeat clickers

Click Rate Drop

8% → <1%

in 12 months

From industry average to our guaranteed sub-1% rate

Employee Sentiment

Positive (97%)

user satisfaction

No more punitive training complaints—only positive reinforcement

These results are based on 500 employees

Get These Results for Your CompanyReady to See the Future of

Security Awareness?

Reclaim your time, end employee frustration, and build a genuinely resilient security culture.

Get Your Personalized Demo

Fill out the form below to see Lora in action.

The Complete Human Risk Platform

From autonomous training to AI-powered offensive security, PhishFirewall provides everything you need to secure your human layer.

Security Awareness

Autonomous training that reduces click rates to <1%.

Phishing Simulations

AI-driven lures adapted to every employee's role.

AI Pen Testing

Secure your AI models and data pipelines from new threats.

PhishEQ

Email security that retracts threats from the inbox instantly.

Risk Analytics

Deep reporting on human risk and behavior change.

Penetration Testing

Full-spectrum offensive security for modern enterprises.

Free Tools Hub

Check your risk for free with our suite of security tools.

Micro-Learning

Engaging, <60 second training in the flow of work.

Frequently Asked Questions

Ready to Secure Your Human Layer?

Join the hundreds of organizations that trust PhishFirewall.

- Free Risk Assessment

- Migration Plan Included

- No Credit Card Required